11/29/2025

"Welcome to Basilisk"

I recently found myself responsible for figuring out how to evaluate satellite attitude control algorithms, purely in software.

Now, I can geek out with the best of them on space and astrophysics, but I haven’t taken it much deeper than “casual interest” since middle school. Meaning: I had no clue where to start. No clue about the tools of the trade, the terms of art, or even what the inputs and outputs of such a system would be.

Luckily, my brief time on this Earth coincides with that of Wikipedia.

The article on “Spacecraft attitude determination and control” is decently readable from a lay perspective, introduces the key concepts and goals in attitude control, and gives examples of the hardware (sensors and actuators) and software that comprise attitude control systems. Here’s my read:

A satellite’s attitude control system is there to keep the craft pointing in the right direction. It involves sensors to measure the current orientation, actuators to change the orientation, and control algorithms to compute the actuator commands that bring the actual orientation towards the target orientation.

This description hints at the contours of an API for our evaluation system:

- a control algorithm is a function from sensor inputs to actuator commands

- the quality of a control algorithm relates to the delta, over time, between measured and target orientation (there may be competing objectives here, such as energy used vs. time spent off-axis)

Implementation

With a sketch of the interface in mind, I wanted to implement a basic example—a simple control algorithm and a scoring function—to start identifying gaps in the API. Sitting down to code, I immediately found my first gap: I needed a physics subsystem to simulate the actual motion resulting from a control algorithm’s outputted actuator commands, to in turn evaluate the delta between real and target orientation.

My options, as I saw them, were to hand-roll a simple attitude dynamics system myself, or to search for an existing framework. I hesitated at first to take the latter path; instead of learning universal physics, I’d just be learning the ins and outs—the very human design choices—of the framework, and all the unused features would introduce accidental complexity and tech debt into an otherwise green system.

I changed my mind when I stumbled on Basilisk.

Basilisk […] is a software framework capable of both faster-than realtime spacecraft simulations […] as well as providing real-time options for hardware-in-the-loop simulations.

The […] framework is targeted for […] astrodynamics research modeling the orbit and attitue of complex spacecraft systems.

The two factors that really sold me were:

- Pre-built modules for all the necessary physics, sensors, and actuators

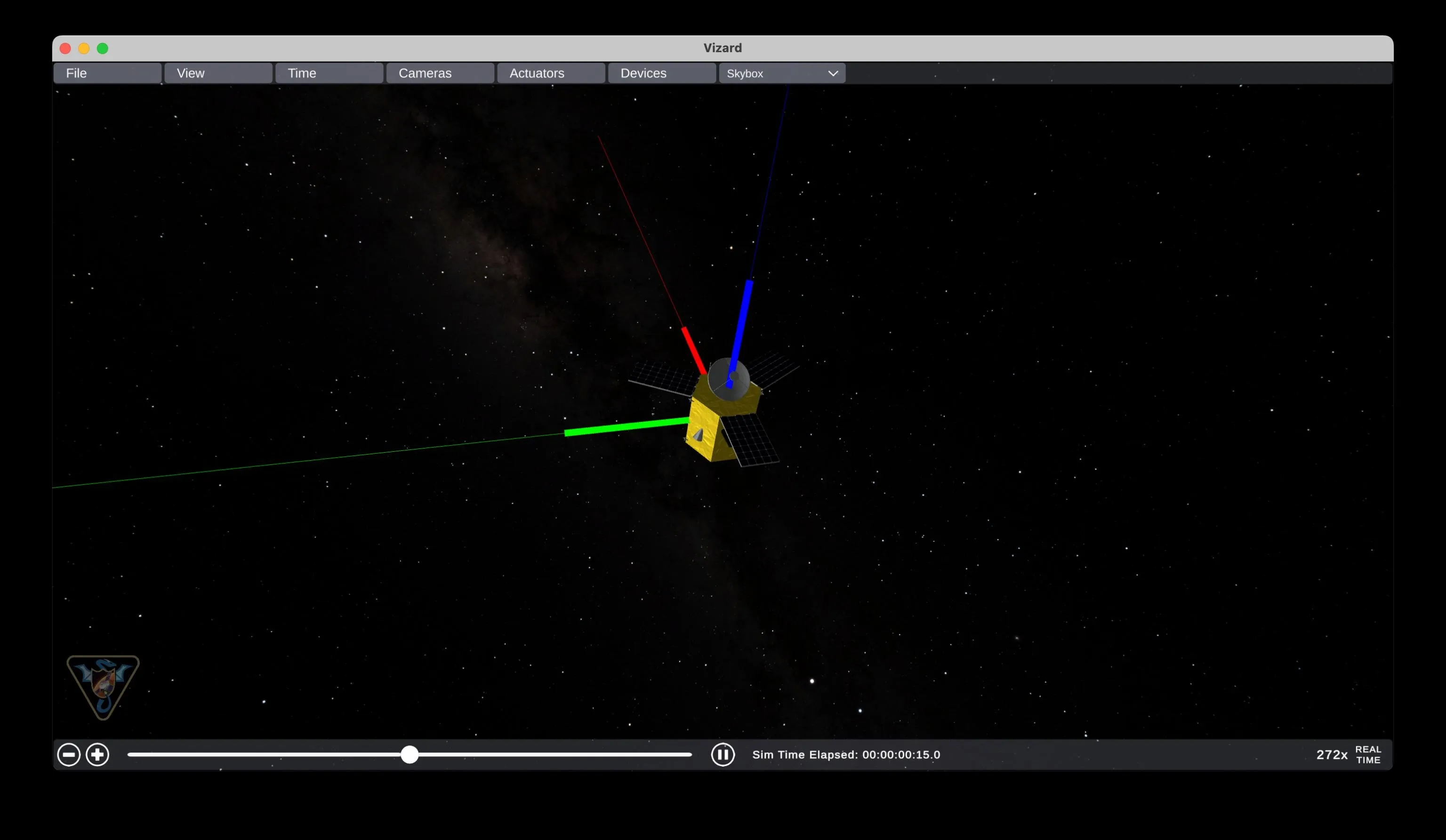

- A companion tool, Vizard, that creates interactive 3D renders of Basilisk simulations. This in particular—an interactive, visual tool—I felt would really help me learn the domain. More on this later (but in the meantime, check out this example video).

Of course, choosing a large, mature, existing framework comes with its own (steep) learning curve, the first hurdle of which was getting the darn thing to run.

Compiling Basilisk: ARM edition

There’s no pre-built Basilisk wheel on PyPI, nor on their GitHub releases. However, work has been done in the last year(-ish) to adopt modern Python packaging techniques, allowing, for example, the following to work:

pixi add bsk --git https://github.com/AVSLab/basilisk.git --pypi --branch develop(Adjust to your Python project tool1. More detail here.)

This command will clone the source code, invoke the Conan/ CMake -based build system

via setuptools to build the underlying C/C++ extensions for your machine’s

architecture, and install the package to the active environment.

A basic simulation

The basic operational metaphors of Basilisk are:

- Modules pass messages to each other

- Tasks execute Modules sharing an update rate

- Processes group Tasks into logical units (e.g. “this satellite” and “that satellite”)

With all that in mind, what does “Hello, world!” look like in Basilisk? Here’s my take, distilled from the first few pages of the “Fundamentals of Basilisk” docs:

from Basilisk.moduleTemplates import cModuleTemplate

from Basilisk.utilities import SimulationBaseClass, macros as bskutil

# (1)

sim = SimulationBaseClass.SimBaseClass()

procDynamics = sim.CreateNewProcess("procDynamics")

procDynamics.addTask(sim.CreateNewTask("taskDynamics", bskutil.sec2nano(5.)))

# (2)

mod = cModuleTemplate.cModuleTemplate()

mod.ModelTag = "cModule1"

sim.AddModelToTask("taskDynamics", mod)

# (3)

sim.InitializeSimulation()

sim.ConfigureStopTime(bskutil.sec2nano(20.))

sim.ExecuteSimulation()- Create the simulation container with a process and a task (nested in that order)

- Create a module and assign it to a task for execution

- Initialize and execute the simulation

Running the above produces the following console output:

BSK_INFORMATION: Variable dummy set to 0.000000 in reset.

BSK_INFORMATION: C Module ID 1 ran Update at 0.000000s

BSK_INFORMATION: C Module ID 1 ran Update at 5.000000s

BSK_INFORMATION: C Module ID 1 ran Update at 10.000000s

BSK_INFORMATION: C Module ID 1 ran Update at 15.000000s

BSK_INFORMATION: C Module ID 1 ran Update at 20.000000sshowing the connection between the task’s update frequency and the simulation’s stop time (note that this doesn’t take 20 seconds to run: Basilisk seems to be smart about timekeeping, allowing it to go “faster-than-realtime”).

A step towards usefulness: messages

The messages our modules emit and consume are our main means to observe the system under test.

sim = SimulationBaseClass.SimBaseClass()

procDynamics = sim.CreateNewProcess("procDynamics")

procDynamics.addTask(sim.CreateNewTask("taskDynamics", bskutil.sec2nano(5.)))

mod1 = cModuleTemplate.cModuleTemplate()

mod1.ModelTag = "cModule1"

sim.AddModelToTask("taskDynamics", mod1)

# NEW: add a second module

mod2 = cModuleTemplate.cModuleTemplate()

mod2.ModelTag = "cModule2"

sim.AddModelToTask("taskDynamics", mod2)

# NEW: mutual connection between mod1 and mod2

mod2.dataInMsg.subscribeTo(mod1.dataOutMsg)

mod1.dataInMsg.subscribeTo(mod2.dataOutMsg)

# NEW: a recorder module for collecting mod2 output messages

modRec = mod2.dataOutMsg.recorder()

sim.AddModelToTask("taskDynamics", modRec)

sim.InitializeSimulation()

sim.ConfigureStopTime(bskutil.sec2nano(20.))

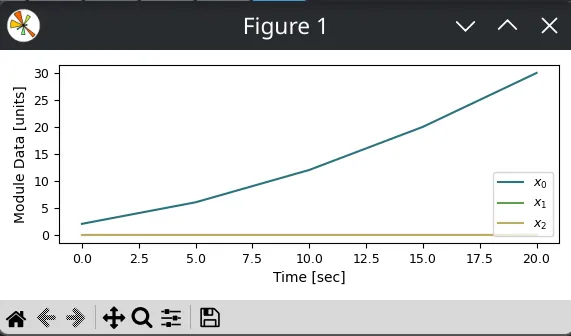

sim.ExecuteSimulation()The attributes of modRec correspond to the attributes of the message type flowing over

the recorded channel. In the case of the recorded cModuleTemplate module, that’s a

single dataVector array, with a row for each recorded message and a column for each of

an arbitrary set of dummy features. Together with modRec.times(), we have X/Y pairs to

plot message values over time:

for feature in range(3):

plt.plot(

modRec.times() * bskutil.NANO2SEC,

modRec.dataVector[:, feature],

)

Visualization

To bring it all together, let’s add a satellite to our “Hello, world!” simulation and see what it looks like in 3D:

from Basilisk.simulation import spacecraft

from Basilisk.utilities import (

SimulationBaseClass,

macros as bskutil,

vizSupport as bskviz,

)

sim = SimulationBaseClass.SimBaseClass()

procDynamics = sim.CreateNewProcess("procDynamics")

procDynamics.addTask(sim.CreateNewTask("taskDynamics", bskutil.sec2nano(5.)))

# NEW: a new module type: *Spacecraft*

modSpacecraft = spacecraft.Spacecraft()

modSpacecraft.ModelTag = "spacecraftBody"

sim.AddModelToTask("taskDynamics", modSpacecraft)

# NEW: emit visualization file for Vizard

viz = bskviz.enableUnityVisualization(

sim,

"taskDynamics",

modSpacecraft,

saveFile="hello-world.bin"

)

sim.InitializeSimulation()

sim.ConfigureStopTime(bskutil.sec2nano(20.0))

sim.ExecuteSimulation()

I think this leaves us at a good stopping point for now. The Spacecraft module

encapsulates the rigid body dynamics I’ll need to simulate axial motion, and supports a

promising-sounding reactionWheelStateEffector module that sounds like just the thing

for comparing attitude control algorithms.

Footnotes

-

A note for other Pixi users: I had to set

[tool.hatch.metadata] allow-direct-references = truein my

pyproject.tomlfor thispixi addcommand to work. ↩